Controversy around the safety of a vaginal birth after C-section has recently prompted sharp declines in this delivery method. Unfortunately, women are often incorrectly told that they’re not allowed to have a vaginal birth after a cesarean section. Known as “VBAC,” vaginal birth after a C-section is an increasingly common way to give birth. But here’s the big problem: Even women who are candidates for a VBAC are often told by their healthcare providers that they must have a repeat C-section for all future pregnancies.

The truth is that medical evidence and national guidelines suggest VBAC is a safe, reasonable and appropriate option for most. In addition, the science shows us that women should be given the opportunity to decide for themselves how they want to handle their childbirth. (1) By getting educated about childbirth and more aware of her options, a mother can reduce fear and stay actively involved in the decision-making process throughout her pregnancy, labor and birth.

What Is VBAC?

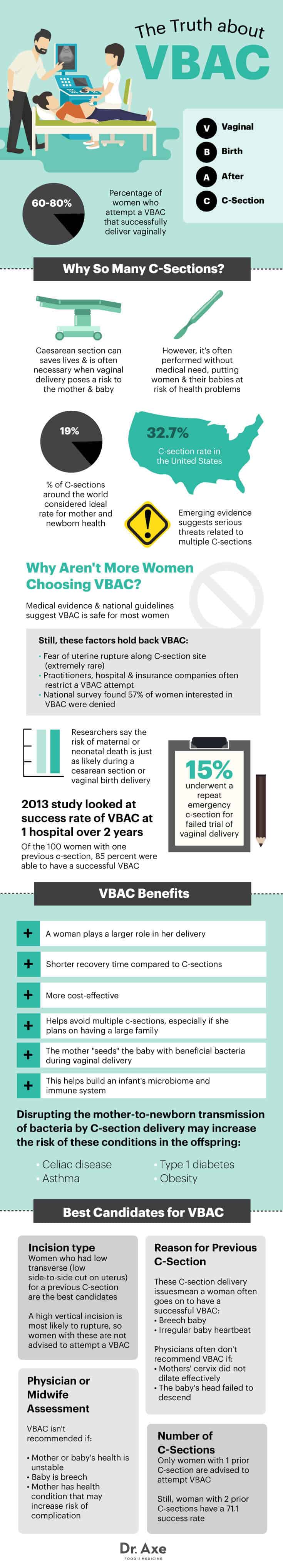

Once a woman has a child delivered by C-section, her options for the next pregnancy are either a planned “trial of labor” or a planned elective repeat cesarean. For many women, a vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) is the best option, as research shows that 60 to 80 percent of women who attempt a VBAC have a successful vaginal delivery.

In the U.S., the C-section rate is 32.2 percent, which is far above the 19 percent believed to be necessary for lower maternal and baby mortality. (3, 4)

There are many reasons why a woman chooses a VBAC: she is able to experience a vaginal birth and play a greater role in her delivery, there is a shorter recovery time for vaginal births compared to c-sections, a vaginal birth is more cost-effective and a VBAC helps a woman to avoid multiple c-sections, especially if she plans on having a large family. (5)

Another major perk of vaginal birth? The baby is “seeded” with an abundance of beneficial bacteria that could possibly help shape the immune system for life. Authors Toni Harman and Alex Wakeford point out in detail intheir upcoming book, Your Baby’s Microbiome: The Critical Role of Vaginal Birth and Breastfeeding for Lifelong Health:

During vaginal birth, as the baby travels through the birth canal, the he or she is coated in the mother’s bacteria. This payload of microbes goes into the baby’s eyes and ears, up its nose and into its mouth. Inevitably, the baby swallows some of the, too.

In the baby’s gut, the first bacteria to arrive start to colonize and multiply. Special breast-milk sugars, called oligosaccharides, are indigestible to the baby, but they are there purely to feed the baby’s newly seeded gut bacteria. This natural “seed-and-feed” process is perfectly designed to set up the baby’s microbiome in the optimal way.

The authors also point out that the latest research indicates that this seed-and-feed process could be critical for the development of the infant immune system. Emerging science suggests that the first bacteria to arrive in the baby’s gut initiate the training of the immune system, helping it to identify what is friend and what is foe (in other words, which bacteria the body should tolerate and which it should attack.) Interfering with this process could result in the incorrect training of the baby’s immune system, in turk resulting in the immune system attacking beneficial bacteria and tolerating harmful bacteria. Overall, this inadequate training potentially sets a pathway for health problems later in the child’s life. Just as the baby develops from a newborn to a toddler, so the baby’s microbiome develops over the first few months and years of life until the microbiome stabilizes some time during early childhood.

A 2013 study published in the North American Journal of Medical Sciences assessed the safety and success rate of VBAC at a hospital over a period of two years. Of the 100 women with one previous C-section, 85 percent were able to have a successful VBAC and 15 percent underwent a repeat emergency C-section for failed trial of vaginal delivery. (6)

Health Challenges Presented by a C-Section

Uterine rupture at the site of the prior cesarean scar is the most feared complication of vaginal birth after C-section. While this is rare (affecting less than 1 percent of women), the consequences to mother and baby are very serious. Uterine rupture is associated with clinically significant uterine bleeding, fetal distress, protrusion or expulsion of the fetus and/or placenta into the abdominal cavity, need for emergency C-section delivery and need for uterine repair or hysterectomy. Although uterine rupture is the most common fear of mothers and caregivers, data suggests that there is a minimal increase in risk of uterine rupture when attempting a VBAC.

A 2012 study conducted at the University of Utah Medical Center found that of the 11,195 trials of labor after cesarean delivery, there were 36 cases of uterine rupture (0.32 percent). In only one case, uterine rupture was not suspected. The babies that were delivered within 18 minutes after a suspected uterine rupture had normal umbilical pH levels and had high Apgar scores (a measure of the physical condition of a newborn infant). Poor long-term outcome occurred in 3 infants with a decision-to-delivery time longer than 30 minutes. (7)

A 2015 study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology analyzed 15,519 women who attempted a trial of labor after 1 previous C-section delivery. Ninety-nine of them experienced a uterine rupture (0.64 percent). (8)

In addition to data showing that uterine ruptures with a first VBAC only happen on rare occasions, after a woman has had a VBAC, her risk of uterine rupture decreases more with each vaginal delivery. The threat of a uterine rupture creates fear in mothers and her family, and in healthcare providers, but researchers suggest that the risk of maternal or neonatal death is just as likely during a cesarean section or vaginal birth delivery.

A 2011 study published in Women and Birth evaluated 21,389 women who delivered a baby in order to gather evidence about the outcomes of VBAC. For women who underwent a VBAC, there was no increase in postpartum hemorrhage, vaginal tears or neonatal complications. Uterine rupture rates were low and researchers concluded that maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with VBAC is comparable to women undergoing vaginal birth for the first time. (9)

Who is a Good Candidate for a VBAC?

There are several factors that a physician or midwife will assess before recommending a VBAC. First is the type of incision a woman had for her previous C-section. There are three types of incisions that may be done during a C-section.

The most common incision is low transverse, which is a side-to-side cut made on the lower part of the uterus. Women with a low transverse incision are the best candidates for a VBAC. The second type of incision is low vertical, an up-and-down incision made in the lower part of the uterus. And then there’s the high vertical incision, which is an up-and-down cut made in the upper part of the uterus. A high vertical incision is most likely to rupture, so women with these are not advised to attempt a VBAC. In the U.S. and many other countries, women with one prior C-section delivery who desire a VBAC must obtain medical record evidence for the type of surgical incision used to determine that there was no vertical incision made on the uterus. (10)

Caregivers also base their recommendation of VBAC on the cause of a woman’s previous C-section. If the C-section was due to something that will mostly likely not be repeated, such as the baby being breech or having an irregular heartbeat, then there’s a greater chance of a successful VBAC. However, if the previous C-section was due to a mother’s cervix not dilating or the baby’s head failing to descend, a physician may not recommend an attempt at a VBAC.

Only women with one prior C-section are advised to attempt a VBAC for their second delivery. Although a woman with two prior C-sections typically isn’t allowed to have a VBAC, research suggests that this doesn’t have to be the case. A 2010 systematic review found that the VBAC-2 success rate was 71.1 percent and the uterine rupture rate was 1.36 percent. Researchers suggest that the maternal morbidity rate is comparative to the rate with a repeat C-section. (11)

Finally, a physician or midwife will want to assess the health of both the pregnant woman and baby before recommending a VBAC. If the baby’s health is unstable or he is breech, a VBAC won’t be recommended. If the mother has a health condition that may increase her risk of complication, such as high blood pressure, most physicians will not attempt a VBAC.

Keep in mind, no hospital or physician has the right to force you to have a surgery that you don’t want. The hospital must first get your consent and physicians cannot operate on you or demand that you have the surgery without it. If you want to try for a VBAC and you feel like you’re being pressured or forced into having a C-section, find a caregiver who will support your wishes. You can also find valuable information on ICAN’s (International Cesarean Awareness Network) website with suggestions on how to address and handle the situation.

4 Steps to a Successful VBAC

1. Pick a Caregiver Who Believes in VBAC

One of the strongest actions you can take to improve your chance of having a VBAC is to pick a caregiver who has a VBAC rate of 70 percent or more. There are plenty of obstetricians and midwives who are committed to providing women with the kind of care they desire and who believe in VBAC. Research suggests that practitioners, hospitals and insurance companies often restrict the option to attempt a VBAC before the patient is consulted about her preferences for mode of giving birth. In a national survey of women who gave birth in U.S hospitals in 2005, 57 percent of mothers who had previous cesareans and were interested in a VBAC were denied the option. This was most often due to unwillingness of their caregiver (45 percent) and the hospital (23 percent), and only 20 percent citing a medical rationale for denial. (12) Because of the trend to discourage or deny VBAC, it is vital that you find a caregiver who believes in this option and will support you throughout the process.

2. Labor at Home

Research has found that cervical dilation of more than 3 centimeters at the time of hospital admission was a significant factor of a successful VBAC. (13) This means that laboring at home for as long as possible increases your chances of having a successful VBAC. Laboring at home also allows you to eat and drink before heading to the hospital (if that’s where you plan to give birth). This will give you the strength you need to labor for hours without interventions. (Interventions increase your chances of needing a repeat C-section.) If you are nervous about laboring at home with just your partner, consider hiring a doula who will come to your house and support you there until it’s time to go to the hospital.

3. Avoid Labor Induction and Augmentation

Labor induction is not prohibited in VBAC labor, but it may pose a greater risk for women hoping to experience a successful vaginal birth. Induction can increase the risk of uterine rupture and according to ICAN, women who undergo an induction of labor with a prior cesarean have a 33 to 75 percent risk of requiring another C-section. An induction should only be considered when it’s medically warranted, otherwise wait until labor begins spontaneously. (14)

A 2004 study published in the Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine analyzed data for 768 women and found that women with successful VBAC had more spontaneous labor and less oxytocin use. (15) If there is pressure for you to dilate more quickly, then move around, change positions and get into water if that’s available. Try to resist interventions like an epidural or synthetic oxytocin for as long as possible and ask your caregiver to keep vaginal exams to a minimum. Skilled practitioners should be able to estimate your dilation based on your breathing and body language.

It is best to avoid interventions because they increase the risk of needing a C-section delivery. Epidural side effects, like slowing down the labor process, may lead to more interventions, like Pitocin (synthetic oxytocin). Pitocin may cause fast or irregular heartbeat for the mother and serious complications for the baby, thereby increasing the chances of delivery by emergency C-section.

4. Take Care of Yourself While Pregnant

The chances of a successful VBAC are higher when a woman and her baby are healthy and the pregnancy is progressing normally. Take care of yourself throughout your pregnancy. Eat a healthy diet that’s based on anti-inflammatory foods, like leafy green vegetables, broccoli, chia seeds, coconut oil, berries, salmon, walnuts and bone broth. Stay active as well — walk often and find a local prenatal yoga class (or use videos and do them at home). Most importantly, stay positive about your VBAC and pride yourself for doing what’s best for you and your baby.

VBAC Precautions

There are some valid reasons for a cesarean section, including:

- a prolapsed cord — when the cord comes down before the baby

- placental abruption — when the placenta separates before the birth

- placenta previa — when the placenta partially or completely covers the cervix

- fetal malpresentation — when the baby is breech or in the wrong position

- cephalopelvic disproportion — when the baby’s head is too large to fit through the pelvis.

- mother’s medical condition — such as severe hypertension, diabetes and/or active herpes lesions

- fetal distress

Some of these conditions are overdiagnosed; for example, sometimes physicians will determine that the baby’s head is too big to fit through the pelvis, but this is caused by the mother’s positioning because she’s lying on her back and isn’t mobile during labor. Fetal distress is also overdiagnosed; research suggests that continuous electronic fetal monitoring increases the C-section rate. (16)

Final Thoughts on VBAC

- A VBAC is a vaginal birth after C-section delivery.

- VBAC frequency has dropped dramatically over the last 20 years and this is due, in large part, to the fear of uterine rupture, even though this is a rare occurrence.

- If you are interested in having a successful VBAC, it is important to find a healthcare provider who believes in VBAC and will be supportive of your decision.

- To increase your chances of a successful VBAC, labor at home for as long as possible, avoid intervention during labor and take care of yourself during pregnancy.